Bailing out airlines without environmental conditions is a monumental mistake

This is the third installment in a series of posts on air travel and climate compensation. You can read the previous posts HERE and HERE.

No doubt the airline industry is in big trouble. The coronavirus pandemic has led most of the world’s airlines to the brink of solvency virtually overnight. In the United States, passenger traffic is down about 94 percent and most airlines have slashed most of their schedules. Combined, the airlines may be losing up to $400 million a day as expenses like payroll, rent and aircraft maintenance far exceed the money they are bringing in.

Now some people predict that the airline industry will never recover, that air travel will never be the same because a lot of people may not want to get on a plane ever again. Of course that’s what many said would happen after 9/11, but it didn’t. I’m sure that air traffic will be reduced in the next year or two, and perhaps some airlines will not stay afloat during the crisis. But it seems reasonable to believe that with time air travel will return to its previous levels — when the pandemic is eventually brought under control, one should add. People want to fly.

But I wonder what the recovery will look like, and to what extent this crisis is an opportunity to chart a more environmentally sustainable future for the airline business. The truth is that before the pandemic hit, many airlines had announced major steps to reduce their carbon footprints. JetBlue became the first major US airline to pledge to offset Co2 emissions from jet fuel for all domestic flights, starting from July 2020. Delta Airlines followed suit soon after.

Now, I’m as skeptical as the next person about airlines going green. Offsetting, as I’ve argued in previous posts, is not a permanent solution. We must work toward solutions that do not put exorbitant amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere in the first place. But while we’re doing that, we also need to mitigate the damage we’re causing now. It’s also important to note that JetBlue announced that it would start flying with biofuel from mid-2020 on all its flights from San Francisco International Airport. In my opinion, biofuel is part of that permanent solution.

More environmentally sustainable air travel can only happen through a mix of economic incentivization for the airlines and government regulation. I don’t believe changing consumer behavior will be strong enough to move airlines in the right direction. Just consider flight shaming, which is strong here in Sweden. There is no evidence that it has caused more than a fractional decline in the number of Swedes flying, and this in a country with a population less than that of Wuhan, China. In many parts of the world, people have just started flying. They’re not going to be shamed into stopping.

On the other hand, there is good evidence that many travelers, particularly in Europe, will choose airlines with stronger commitment to more environmentally sustainable practices. According to a consumer research study by Finnair, and reported by Greenaironline.com, almost all Finns – 94% – want to reduce the emissions from their air travel and three-quarters are willing to pay extra as part of the ticket price, but want the charge to be used directly for environmental purposes. Clearly the decisions of JetBlue and Delta and other airlines that have pledged to become carbon neutral were driven by economic incentives.

I don’t see anything wrong with that, nor that they were taking these steps because they could afford to. Delta, for example, posted $1.6 billion in profits last year, making it the most successful year in the company’s history. While I don’t think a company like Delta needs to wait until it makes billions in profit before doing the right thing, I’m glad it eventually did. The problem, of course, is that the economic devastation wrought by the corona pandemic has thrown all of the environmental thinking out the window. The airlines have other things to worry about.

This is where the regulation part comes in. Critics of the government bailout of the airlines in the United States, which passed in late March to the tune of $58 billion, rightly pointed out that companies that for the last few years spent their record profits buying back stock didn’t deserve taxpayer help. They could have just sold their stock, which seems like a perfectly reasonable argument. But the greater travesty in my opinion is the missed opportunity that the bailout presented to enact some meaningful environmental legislation. The Democrats in Congress wanted to require airlines to cut carbon emissions in return for the aid, but to absolutely no one’s surprise the Republicans squashed those proposals. What a waste!

At least in Europe there is talk about environmental components of the €26 billion airline bailout, even if people like the German environment minister says idiotic things like now is not the moment to green a Lufthansa bailout. Austrian officials have said any bailout for Lufthansa subsidiary Austrian Airlines should come with climate conditions. France announced a €7 billion bailout of Air France with some environmental conditions, including that the airline cut its carbon intensity by 10 percent from today’s levels in 2030, halve CO2 emissions from flights within mainland France, and use at least 2 percent of alternative jet fuel by 2025.

It’s something. And at least organizations like Greenpeace and Carbon Market Watch are mobilizing to track the bailouts. You can check out the tracker HERE. Covid-19 is no doubt forcing a reboot of the aviation industry, It would be good to make it a lasting one that works for the planet as well.

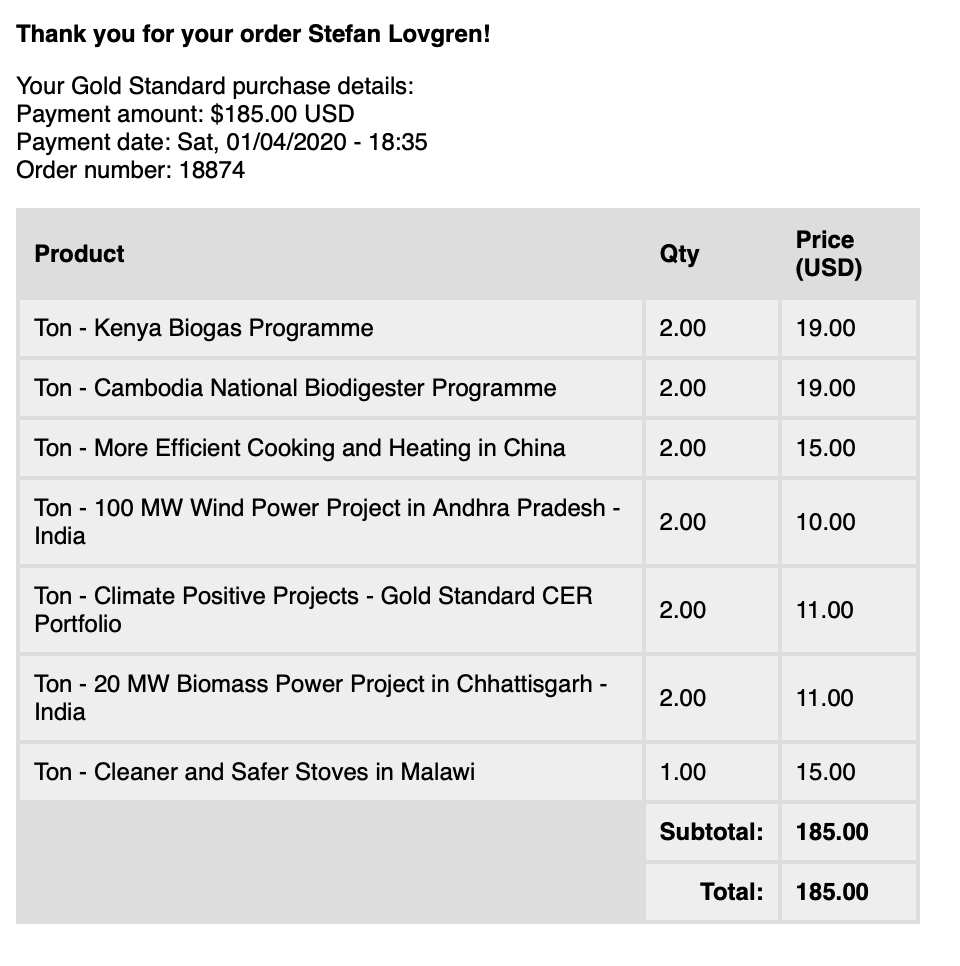

In the meantime, I’m stuck at home. Soon it will be three months since I returned from a reporting trip to Kenya, which may be the longest I’ve gone without flying for, well, a long time. At the beginning of the year I paid my climate dues for the flights I took last fall, using the same calculation method as before (climatecare.org) and buying credits in projects offered through goldstandard.org.

Earlier in the year, before the pandemic hit, I traveled to Washington, DC for work, before going to Kenya. I decided to compensate for these trips by buying credits in the Kenya biogas program that I have previously contributed to and which I’m hoping to visit next time I go to Kenya. Below is the description of the project, and here is a helpful YOUTUBE VIDEO.

Domestic biodigesters provide a way for households with livestock to reduce their dependence on polluting firewood and expensive fossil fuels. Cooking on biogas is fast and smokeless, improving family health, especially among women and children. Leftover slurry from the biogas process is an excellent organic fertilizer that improves crop yields – and having more vegetables to sell, provides families with extra income.

The Kenya biogas programme provides biodigesters to individual households. The programme is part of the Africa Biogas Partnership Programme (ABPP). ABPP is a partnership between the Dutch government, Hivos and SNV Netherlands Development Organization, in support of national programmes in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia and Burkina Faso. The overall objective is to develop a commercially viable biogas sector that supports the use of domestic biogas as a local, sustainable energy source.

Since the start of the programme in 2009, over 15,000 biodigesters have been built across Kenya. Entrepreneurship is encouraged and, to date, nearly 100 masons have started their own business entities, helping to build the local economy.

A barrier for some families is the cost to apply the biogas technology, the programme has therefore initiated credit partnerships with financial institutions. Working together with rural micro finance institutions and saving cooperatives, it ensures that biodigester buyers get the most favorable credit terms. Income from carbon credit sales benefit directly biogas users in forms of after-sales support, bioslurry training and other useful services.

Project impacts and benefits (until December 2018):

15,140 smoke-free kitchens

90,840 direct beneficiaries

333,500 tCO2 reduced

202,000 ton of wood saved

14,200 productive slurry users

28 private enterprises

115 full time jobs plus part-time unskilled day labour