Climate compensating or offsetting means calculating emissions and then purchasing equivalent “credits” from projects that prevent or remove the emissions of an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases elsewhere.

THIS IS PART 2 IN A SERIES OF POSTS ON CLIMATE COMPENSATION.

I’m going to climate compensate for air travel I’ve made since November 1, 2018, as well as holiday flights of my family members during that time.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) reports that only one percent of airline passengers worldwide offset their carbon emissions through voluntary programs. However, the practice saw a 140-fold growth between 2008 and 2018, and 430 million tons of emission reductions have been generated since 2005. Climate compensation for air travel is getting more media attention, too, though I’m surprised the subject is not covered regularly by more news outlets. John Vidal recently wrote a good article for The Guardian on how the business has changed:

A decade ago, the voluntary carbon offset market was tiny, unsophisticated and largely unregulated. The little money raised was aimed at worthwhile projects, but few schemes to cut emissions or promote development were verified or certified. Exposés, the financial crash and painfully slow progress in the UN climate talks all helped discourage individuals and companies from offsetting. But as awareness of the climate crisis has grown, corporates in particular have turned to voluntary offsetting and sent the market mainstream. Small companies have been weeded out, highly regulated global carbon and renewable energy markets have been set up, and thousands of participating companies and charities are now theoretically held to international standards by independent verifiers.

Here are the flights I’ve taken since Nov. 1, 2018:

Stockholm – Munich – Mexico City – Frankfurt – Stockholm

Stockholm – Frankfurt – San Francisco – Frankfurt – Stockholm

Stockholm – Doha – Phnom Penh – Doha – Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh – Bangkok – Buriram – Bangkok

Bangkok – Chiang Mai – Phnom Penh

Stockholm – Bergamo – Stockholm (5 passengers)

Stockholm – Helsinki – Singapore – Phnom Penh – Beijing – Stockholm

Stockholm – Delhi – Stockholm

Delhi – Guwahati

Paro – Katmandu – Delhi

Stockholm – Addis – Entebbe – Addis – Stockholm

Stockholm – London – Austin – Los Angeles – Helsinki – Stockholm (5 passengers)

Stockholm – Frankfurt – Sao Paolo – Frankfurt – Sao Paolo

To calculate my emissions from these flights, I used a climate compensation calculator. There are lots of calculators available online with which people can calculate their carbon footprints from air travel.

Most calculations are made based on cargo, passenger and fuel consumption data, taking into consideration factors such as seat occupancy on a flight to come up with an individual emission figure. With some calculators, you can specify the type of airplane used for the flight. A business ticket doubles the emission amount compared to a ticket in economy.

What complicates things is that the CO2 generated does not account for the total warming effect. There is, for example, the issue of radiative forcing, which is explained here. There are also other emissions apart from CO2, such as nitrogen oxides and water vapor, which contribute to global warming. Some calculators take these contributing factors into account, while others don’t.

I figured the best way was to research and visit as many carbon offsetting sites as possible and settle on the few that got the best reviews, were easy and understandable to use, and made comprehensive calculations. The ones I selected were:

MyClimate.org (Swiss-based)

ClimateCare.org (UK)

CarbonFootPrint.com (UK)

Atmosfair.de (German)

Klimatkompensera/tricorona.se (Swedish)

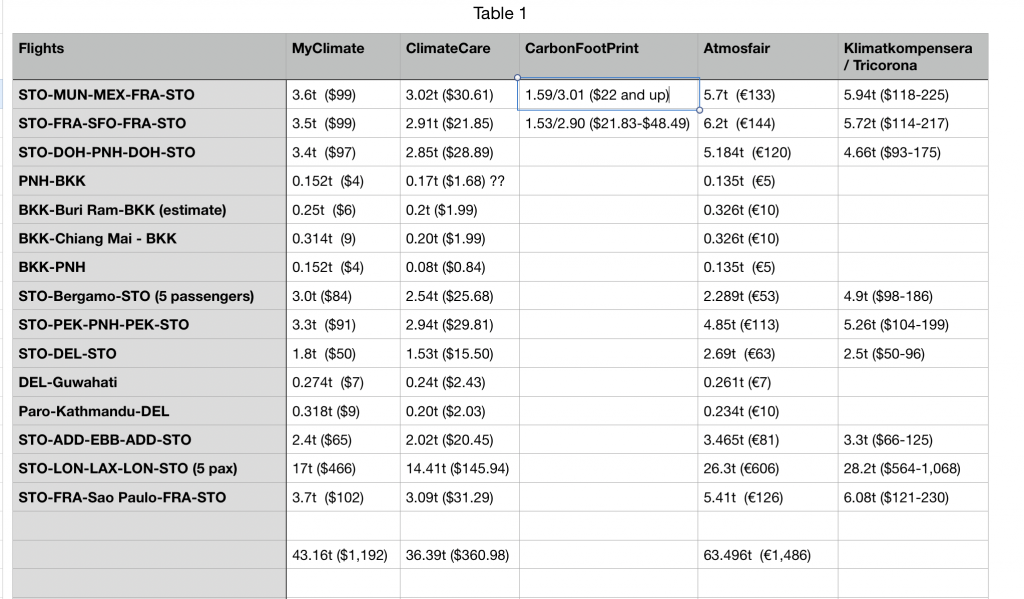

Here is a spreadsheet showing the amounts of carbon calculated for my trips by each offsetting company. (Also included are the credits in dollar amounts, which I’ll explain further down.)

The table shows that my flying roundtrip from Stockholm to Mexico City via Frankfurt (I actually traveled via Munich to Mexico and via Frankfurt back, but none of the calculators would allow me to use two different airport stopovers, so I used Frankfurt for both ways) caused 3.6 tons of carbon emissions, according to MyClimate; 3.02 tons, according to ClimateCare; 1.59 tons without radiative forcing adjustment and 3.01 tons including it, according to CarbonFootPrint; 5.7 tons, according to Atmosfair; and 5.94 tons, according to Tricorona.

The reason the values for a flight with Atmosfair, for example, are higher than other emissions calculators is in part because that company multiplies the CO2 emissions emitted at altitudes over 9 km (to compensate for radiative forcing) by a factor of 3, which is far higher than what other companies use.

There were various reasons for why I did not choose certain sites. Greentripper would not let me include stopovers; Chooseclimate.org had a website that looked like it was stuck in 1995. I also had a lot of trouble using the calculator for the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), and in any case the numbers that it produced seemed way too low.

The most user-friendly calculators were MyClimate and ClimateCare, which may explain why they are also two of the most popular sites available. Both of these companies have been around for a while; ClimateCare achieved its first million tons of CO2 reductions in 2007 and since 2011 it has deployed over $100 million. The two sites came up with relatively similar emission values for my flights, with MyClimate’s numbers 10-20 percent higher on average. Total carbon emissions on MyClimate were 43 tons, while ClimateCare had me at 37 tons. So I decided to split the difference and put the total amount at 40 tons.

Next I had to choose which carbon offsetting projects to support. This is also a little tricky, as there is a lot of debate about what actions best reduce emissions. Tree planting is popular, but there have been a lot of problems with some forestation offset schemes, including displacement of people. You’re also offsetting immediate emissions with reductions that occur only during the entire life span of a tree, which can be more than 100 years.

Wind and solar power projects are usually widely welcomed on a community level, while capturing methane gas from waste tips and landfill sites makes sense but isn’t that sexy. The most important thing to establish is that the offset project is in addition to the normal course of business. If, for example, your credit is supposed to help pay for a new wind farm, but then you learn that the wind farm was going to be built anyway, without the help of offsets, you would feel cheated and rightly so.

There are, however, several organizations that approve and certify climate projects. The largest standards are CDM (which the UN is behind), Gold Standard (which the World Wildlife Fund and others support), Plan Vivio, VCS and Fair Trade. All the reputable companies use verification by these standards for their projects. I like the Gold Standard Foundation, because I understand its projects are more audited by independent third parties than, for example, projects that are only UN-certified.

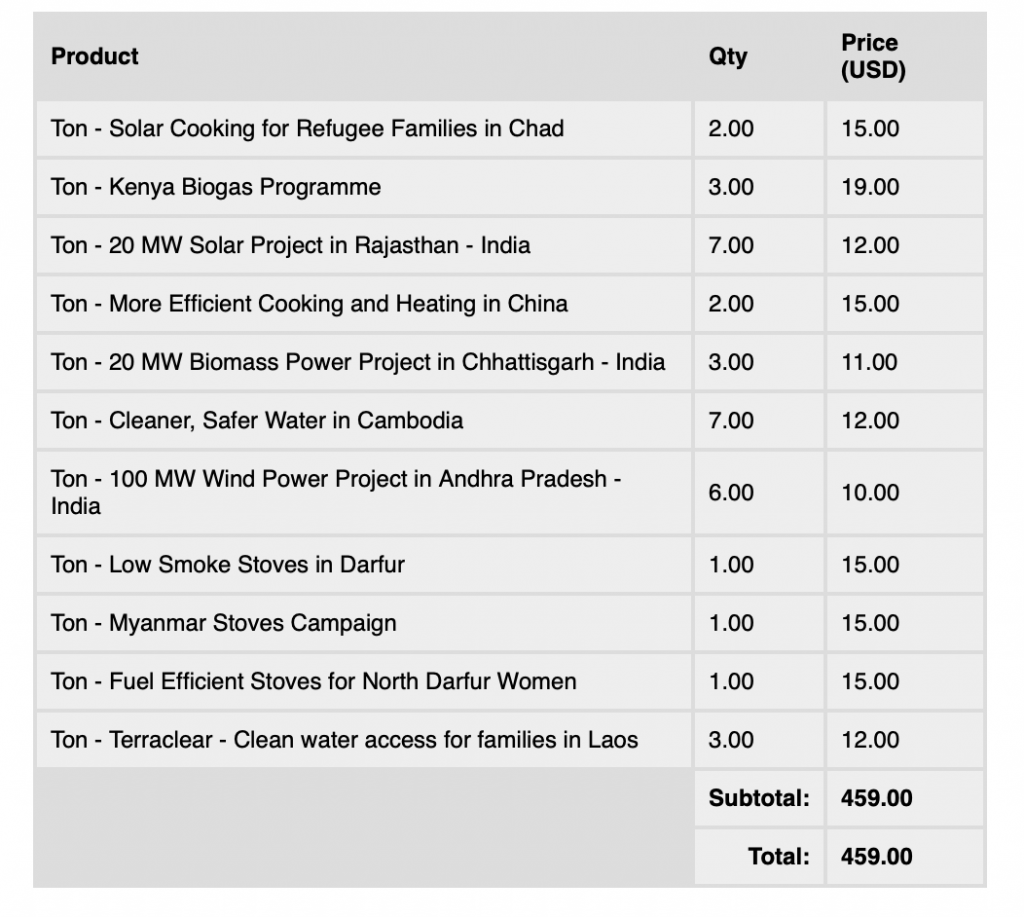

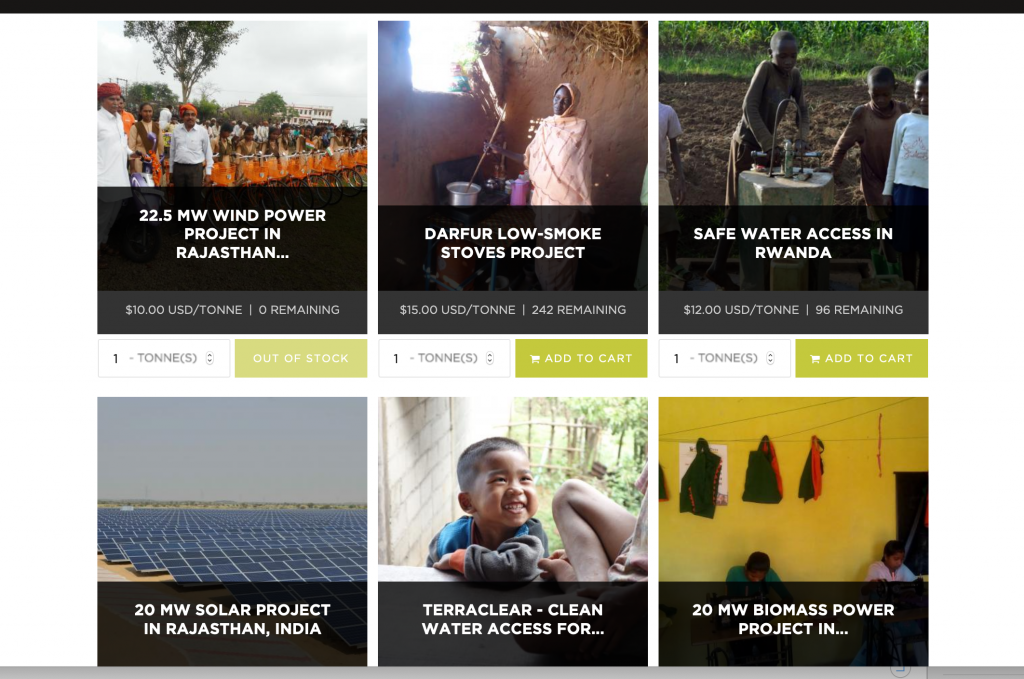

In fact, since I had already calculated my emissions (using the MyClimate and ClimateCare calculators), I chose to purchase offsetting credits directly from the Gold Standard Foundation rather than from those sites. (In the previous table, the dollar amounts listed next to the emissions value for each flight are the cost of offsetting that flight if you buy the credits from that company.) The reason I went with the Gold Standard directly was because it had a wider range of projects offered, and several that I found personally attractive.

In the end, I decided on the following projects. Total cost: $459.